- Identification

- Edibility

- Nutrition

- How to cook

- Stinging nettle tea

- Range

- Habitat

- Traditional uses

- How to harvest

- How to process

Identification

Stinging nettle (Urtica genus) is a European native plant that has become naturalized throughout the United States. It's considered an aggressive invasive and has become established and common in certain areas.

Nettles grow 2 to 5 feet tall and have opposite leaves.

The leaves are coarsely toothed, pointed on the ends, and can be several inches long.

Stinging nettles (Urtica dioica)

Smaller, younger leaves are more heart-shaped.

True to its name, stinging nettle imparts a painful sting through tiny hairs on the underside of its leaves and on its stems.

The stinging hairs, called trichomes, are hollow like hypodermic needles with protective tips.

The tips break off when touched, unsheathing the sharp needles.

The trichomes inject formic acid, histamines, and other chemicals into your skin, which is what causes the sting.

Stinging nettle is dioecious, which means plants can have either male or female flowers.

The tiny flowers are arranged in inflorescences that hang off the stems like catkins.

Male flowers can be yellow or purple, while female flowers are green and white.

Stinging nettle resembles clearweed (Pilea pumila), a non-toxic but unpalatable plant, but clearweed has no stinging hairs.

Edibility

For centuries, nettle has been a staple for ancient cultures and continues to be an important food source throughout the world.

It's arguably one of the most nutritional wild edibles available, but it needs to be cooked or dried to neutralize the sting.

Nutrition

The researchers blanched nettle leaves for one minute, drained, and dried at 60°C (140°F) for two days and then ground the dried leaves into flour.

They reported that nettle leaf flour had three times more protein than wheat or barley and less than half the carbohydrates.

Nettle also had "a range of health benefitting bioactive compounds" and "a better amino acid profile than most of the other leafy vegetables".

According to the USDA's food nutrient database, 100 g of blanched stinging nettle has an average of 481 mg of calcium and 6.9 g of fiber.

That's 37% of the daily value for calcium and 25% for fiber, according to nutritionvalue.org.

Cooking

Prepare nettle leaves as you would spinach — lightly steamed, sautéed, in stir-fries, soups, etc.

Or try making fresh stinging nettle pasta.

Be careful not to overcook which will destroy nettle's nutritional qualities and result in an unappealing mush.

The best ways to use nettle are fresh, tinctured, or freeze-dried, but air-drying or dehydrating works, too.

Tea

The easiest way to get the benefits of nettle is to steep the fresh leaves in hot water for an earthy hot tea.

Simply harvest a handful of leaves, cover with boiling water, and let steep for ten minutes or so. Then strain and drink.

Or for a stronger brew, make an infusion by loosely filling a Mason jar with nettle leaves, cover with boiling water, cover the jar, and let steep overnight.

Fresh mint is great for enhancing the earthy flavor.

You can also make bigger batches to store in the fridge for a couple days to drink cold or re-heated.

If you have any left over and don't want to store it, pour it on your plants...they really love the silica in nettle tea.

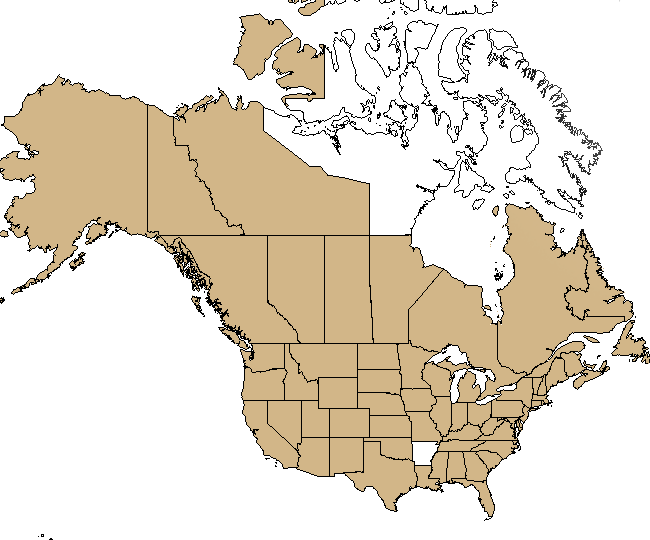

Range

Stinging nettle has naturalized in nearly every state in the United States.

According to the USDA's range map, it (Urtica dioica) has not been confirmed in Arkansas.

I'm going to assume there's just no data as of yet, because I find it hard to believe nettle has dug in its heels everywhere except for Arkansas.

Habitat

Nettles thrive in damp, nitrogen-rich soil; look for it in bottom land along rivers and streams, around old farm-steads, and in other full-sun to partially shaded areas with well fertilized dirt.

When you find it, you'll usually find it in a dense stand.

Our native wood nettle (Laportea canadensis) has similar qualities, though it favors the shade of forest canopy and grows in more sparsely populated colonies.

Wood nettle is harder to gather in quantity and it's more susceptible to the pressure of over-harvest.

Traditional uses

Not only is nettle an excellent food source, but it also has a long history of use as a fiber.

Its tough, fibrous stalks have been made into paper, cordage for fishing nets and rope, and linen-like cloth.

In 2012, archaeologists in Denmark discovered scraps of a 2800-year-old Bronze Age burial shroud that were made of wild nettles.

Nettle leaves also make a greenish dye, while the roots were used traditionally as for yellow dye.

How to harvest

The most important consideration for harvesting nettle is NOT to eat it after it flowers in late spring. Once nettle flowers and goes to seed, the plant produces an alkaloid that could be harmful to the kidneys when consumed in quantity.

Early spring is the best time to harvest — I try to pick more early in the season and store for later use.

Like most edible plants, the best way to eat nettle is to consume it shortly after being harvested.

Pick only the tenderest, youngest leaves. Pinching off the top of the plant is a great way to take only tender new growth while leaving most of the plant to continue growing.

Stands of nettle tend to be so dense that it's really easy to pick a lot quickly. Considering the economics of your time, nettle is one of the more valuable wild edibles.

I should mention, too, that the best way to pick nettle is with scissors and rubber dishwashing gloves, since they're long enough to cover part of your arms and wrist.

Rose gloves are a better alternative since they'll last longer, but they're more expensive. Long sleeves and work gloves will work, too.

A big bowl or basket is also really helpful -- just cut the tops straight into your bowl.

No matter how much armor you wear, though, it's nearly impossible to avoid getting stung. The stinging hairs seem to have a knack for finding any square millimeter of minimally guarded skin.

The sting typically doesn't last long, but it when it stings, it really stings.

Rubbing the affected area with jewelweed or plantain can help relieve the sting.

How to process

Freezing is the best method for putting nettle away to use later, especially for eating. There are a few techniques that work well:

- Blanch whole leaves and pack in freezer bags or plastic containers and freeze.

- Freeze tea in plastic freezer containers. This is better than making tea from dried nettle but it obviously takes a lot of space and isn't practical unless you live in an igloo, in which case you probably don't have access to fresh nettle.

- Puree fresh leaves, steep in hot water, let cool, pour into ice cube trays, and freeze. Put the cubes in hot water to thaw and sip as tea or add them to green smoothies later. You could also make pesto with nettle and freeze in ice cube trays.

- You can also dry and store nettle leaves for later use in capsules or tea, but dried nettle is far inferior to fresh or frozen.

Conclusion

I love the fact that stinging nettle is such a nutritional powerhouse and such an effective remedy for allergies and it's so freely available.

It's a great plant to keep around the urban or rural homestead, as long you keep it from taking over your garden or yard.

I love knowing that the negative impact of over-harvest isn't really an issue since it's so invasive where I live and throughout the U.S.

I'm actually doing the ecosystem a favor by harvesting nettles!

Comments

Hello -

We just returned from backpacking in Shenandoah National Park, where we were accosted constantly by stinging nettles. Of course we've always heard they are edible, so that led to this google search and your fantastic page! Quick question due to our recent experience. Do you do anything to try to remove the nettles before making tea or cooking/drying? These little needles wrecked havoc on our exposed legs and the thought of drinking them or putting them in our mouth seems scary. Does the heating up process do something to eradicate the sting? Last thing I want to do is drink a glass of tea only to swallow a bunch of dislodged nettle needles! Thanks.

You don't need to do anything special before cooking or drying. Cooking, soaking, or drying will neutralize the sting -- it's not really the needles that cause pain, but the chemicals they inject. I'm guessing the process also softens or degrades the needles because they're not an issue.